Universal Design Principles and Guidelines

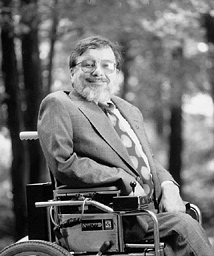

Universal design ensures that products and buildings can be used by virtually everyone, regardless of their level of ability or disability. The late Ronald L. Mace, a fellow of the American Institute of Architects, coined the term universal design. It means designing all products, buildings, and exterior spaces to be usable by all people to the greatest extent possible. Universal design is not a design style, but an orientation to design based on the these principles:

- Disability is not a special condition of a few;

- It is ordinary and affects most of us for some part of our lives;

- If a design works well for people with disabilities, it works better for everyone;

- Usability and aesthetics are mutually compatible.

Thus, through applying the principles of universal design museums can better accommodate visitors with disabilities and engage their entire communities. Universal design can help museums become more inclusive.

In 2001, after t en years of research the World Health Organization issued the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), a framework for describing and measuring health and disability. The ICF puts the notions of “health” and “disability” in a new light. It acknowledges that every human being can experience a change in health and thereby experience some degree of disability. In other words, disability is not something that only happens to a minority. The ICF thus “mainstreams” the experience of disability and recognizes it as a universal human experience.

en years of research the World Health Organization issued the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), a framework for describing and measuring health and disability. The ICF puts the notions of “health” and “disability” in a new light. It acknowledges that every human being can experience a change in health and thereby experience some degree of disability. In other words, disability is not something that only happens to a minority. The ICF thus “mainstreams” the experience of disability and recognizes it as a universal human experience.

By shifting the focus from cause to impact it places all health conditions on an equal footing allowing them to be compared using a common metric – the ruler of health and disability. Using the ICF reasoning, having a cold, angina, or suffering from depression are all on equal footing.

Furthermore ICF takes into account the social aspects of disability and does not see disability only as a “medical” or “biological” dysfunction. By including Contextual and Environmental Factors, ICF records the impact of the environment on a person’s functioning and supports the development of universal design – the creation of products and environments that are usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.

Thinking about universal design encourages us to see that the environment is multi-layered and includes physical, information, communication, policy, and attitudinal/social environments. The Institute on Human Centered Design now defines a user or expert as “a person who has developed expertise by means of their lived experience in dealing with the challenges of the environment due to a physical, sensory or cognitive functional limitation.”

The Institute defines a primary user or expert as one who “personally lives with one or more functional limitations, and secondary users or experts as “a friend, spouse, family member, service provider, therapist, teacher, or anyone who has extensive experience sharing life with primary users or experts and paying close attention to the interface with their environments.”

Universal Design is based upon Seven Principles

1. Equitable Use: The design is useful and marketable to any group of users.

- It provides the same means of use for all users: identical whenever possible; equivalent when not.

- It avoids segregating or stigmatizing any users.

- It provides privacy, security, and safety for all.

- The design is appealing to all users.

2. Flexibility in Use: The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

- It provides choice in methods of use.

- It accommodates right or left-handed access and use.

- It facilitates the user’s accuracy and precision.

- It provides adaptability to the user’s pace.

3. Simple and Intuitive Use: Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills or current concentration level.

- It eliminates unnecessary complexity.

- It accommodates a wide range of literacy and language skills.

- It arranges information consistent with its importance.

- It provides effective prompting and feedback during and after task completion.

4. Perceptible Information: The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities.

- It uses different modes (pictorial, verbal, tactile) for redundant presentation of essential information.

- It provides adequate contrast between essential information and its surroundings.

- It maximizes “legibility” of essential information.

- It differentiates elements in ways that can be described (i.e., make it easy to give instructions or directions).

- It provides compatibility with a variety of techniques or devices used by people with sensory limitations.

5. Tolerance for Error: The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintentional actions.

- It arranges elements to minimize hazards and errors: the most used elements are the most accessible; hazardous elements are eliminated, isolated, or shielded.

- It provides warnings of hazards and errors.

- It provides fail safe features.

- It discourages unconscious action in tasks that require vigilance.

6. Low Physical Effort: The design can be used efficiently and comfortably and with a minimum of fatigue.

- It allows user to maintain a neutral body position.

- It uses reasonable operating forces.

- It minimizes repetitive actions.

- It minimizes sustained physical effort.

7. Size and Space for Approach and Use: Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation and use regardless of user’s body size, posture or mobility.

- It provides a clear line of sight to important elements for any seated or standing user.

- It makes reaching to all components comfortable for any seated or standing user.

- It accommodates variations in hand and grip size.

- It provides adequate space for the use of assistive devices or personal assistance.

The Smithsonian Guidelines for Accessible Exhibition Design details how exhibition content, label text and design, and audiovisuals and interactives can be accessible. It also specifies the circulation route, exhibition furniture, color, lighting, public programming spaces, children’s spaces, and emergency egress.

The Standards Manual for Signs and Labels (by Anna-Marie Kellen, 1995) is useful for signs and labels that address the needs of wheelchair users and visitors who are blind or have low vision.